Whale bones unearthed at Roman ruins suggest the animals were hunted by humans as long as 2,000 years ago.

Genetic fingerprinting evidence points to the presence of right and grey whales in the Mediterranean Sea, where they may have been targeted by Roman fishing fleets.

Until now, the Basque people were thought to be the first commercial whalers from the 11th Century onwards.

However, the new discovery suggests whales were exploited long before then.

Researchers identified right and grey whales from bones at Roman sites in the Strait of Gibraltar area using genetic fingerprinting.

The Strait of Gibraltar is the entry point into the Mediterranean Sea from the Atlantic Ocean.

The whales may have entered the Mediterranean Sea to give birth, roaming far from what was thought to be their historical range.

The Gibraltar region was the centre of a massive fish-processing industry in Roman times. Products such as salted fish were exported to faraway parts of the Roman Empire.

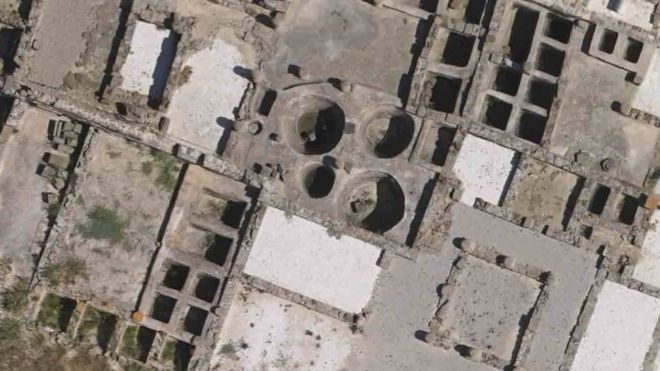

The ruins of hundreds of factories with large salting tanks can still be seen today in the region.

If the Romans were exploiting fish such as tuna, they might also have been catching whales with boats and hand-held harpoons to supply whale products such as meat and fat.

The presence of large whales along the shores of the Roman Empire suggests that the Romans would have had access to grey and right whales.

These would have been easier to hunt than faster-moving sperm or fin whales, which are commonly found in the Mediterranean Sea.

"This is the first identification of these two species within that basin," said Dr Camilla Speller of the University of York, one of a team of UK and French scientists that analysed the bones. Read More

Ancient Fish Salting Tanks