Around 100 million years ago, grass from land adapted to live and reproduce while submerged in seawater—the modern-day seagrasses. This sea invasion by land plants happened four separate times, resulting in four unrelated families of 50-60 total seagrass species, which can be found on the coast of every continent except Antarctica. Just like grasses on land, seagrasses form vast meadows, produce flowers and seeds, and are home to an incredibly diverse community of organisms.

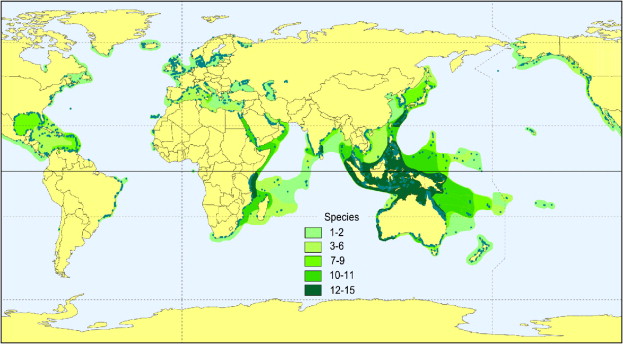

Seagrasses are found around the world, in tropical and colder regions. Shades of green indicate numbers of species reported for an area.

Seagrass meadows, such as this one composed of turtle grass (Thalassia testudinum and manatee grass (Syringodium filiforme), are an important shallow water habitat.Seagrasses get their energy from photosynthesis—converting sunlight into energy—and so must live in shallow water touched by the sun.

There they grow into lush meadows not just by reaching blades upwards, but also stretching their roots down and sideways. Many stems in a meadow are a single plant, connected underground by their roots in what’s known as a rhizome root system. In some seagrass species, a meadow can spring up from a single plant in less than a year; in slow-growing species, it can take hundreds of years.

Since they are true flowering plants (angiosperms), seagrasses reproduce by pollinating flowers and sending out seeds. Male flowers release pollen into the water that often collects into stringy clumps and, moved by the waves, runs into and fertilizes female flowers. Just like land plants, these flowers develop into seeds, which can float many miles before they settle onto soft seafloor (a few species can settle on rock) and germinate into a new plant. For more information on this important habitat click here

For more information on this important habitat click here